What Was The Racial Makeup Of Most Of The Free People Of Color?

Effects of the Racial Makeup of Juries

Compiled by Alicia Arman, Avery Cummings, Kezia Osunsade, Julian Ross, Starlin Shi

Introduction: In function because of the prosecutor's peremptory challenges, Curtis Flowers'southward juries were either all-white or predominantly white. The Petitioner's legal question, whether DA Evans violated the Supreme Court's 14th Subpoena prohibition on race-based peremptory challenges during jury pick to create an all-white jury, hinges on a research question: What consequence, if whatever, do all-white juries have on the outcome of cases like Mr. Flowers' (capital cases with defendants of color)? What consequence, if any, practice racially diverse juries have on the same cases?

Two quick introductions to the case can exist found here:

- ScotusBlog

- New York Times

In Flowers five. Mississippi, Curtis Flowers volition challenge the Mississippi Supreme Courtroom's failure to observe a Batson violation by the prosecutor at his sixth criminal trial. Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986) disallows the hitting of prospective jurors on the basis of race. Flowers will contend that the Mississippi Supreme Court failed to consider the prosecutor'south history of racial bigotry in jury selection in evaluating the Batson claim, and that, if they had, the Courtroom would accept found discrimination.

Batson v. Kentucky, a landmark Supreme Court case, holds that the Equal Protection Clause forbids prosecutors from challenging potential jurors solely on account of their race or on the supposition that black jurors equally a group volition be unable to impartially consider the Land's case against a blackness defendant. Batson 5. Kentucky, 476 U.Southward. 79 (1986). This outcome is usually regarded equally a triumph as well every bit a cultural criterion: it coined the now-vernacular terms "Batson rule" and "Batson violation," and seemingly signaled a much-needed overhaul of trial practices.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment bars the exclusion of jurors on the basis of race. Pena-Rodriguez five. Colorado, 137 Due south. Ct. 855, 868 (2017) (citing Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879). For a defendant, the jury serves as a "vital cheque against the wrongful exercise of power by the state," Pena-Rodriguez, 137 Southward. Ct. at 859, and for the community at large, the jury creates an impression of fairness and legitimacy within the criminal justice system. Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.Due south. 400, 413 (1991). As the jury is to be "a criminal accused's fundamental 'protection of life and liberty confronting race or colour prejudice,'" McCleskey 5. Kemp, 481 U. Due south. 279, 310, 107 S. Ct. 1756, 95 Fifty. Ed. 2d 262 (1987) (quoting Strauder, supra, at 309, 25 L. Ed. 664), permitting racial prejudice in the jury arrangement amercement the jury'due south off-white decision-making and the perception of the jury as fair within the community, Pena-Rodriguez, 137 S. Ct. at 868. Farther, racial discrimination in the jury system is harmful to wrongfully excluded prospective jurors, equally the exclusion is an "assertion of their inferiority" by the legal system. Strauder, 100 U.S. at 308.

To decide how federal courts were sidestepping Batson, Jeffrey Brand examined several federal commune court cases for how they apply Supreme Court preemptory challenge jurisprudence; it explains how lawyers get effectually the Courtroom's prohibition of race-based preemptory challenges. In Flowers, District Attorney Doug Evansused some of these tactics to circumvent the Court's control in Batson. He is not alone in deploying these tactics to ensure a racially discriminatory jury selection procedure: in 1994, Brand explained that this technique "is consistent with the federal judiciary's deemphasis on the outset stage of Batson'south methodology. That is, circuit courts are increasingly focusing on the proffered neutral explanation without fifty-fifty deciding whether a prima facie case exists. Thus, before April 1990, the federal courts took this route in seventeen of 120 cases (14%). After Apr 1990, however, neutral reasons were considered in thirty-6 of 120 (30%) cases despite the fact that no determination had been made with respect to the being of a prima facie case." Jeffrey S. Brand, The Supreme Court, Equal Protection, and Jury Selection: Denying that Race Even so Matters, 1994 Wis. L. Rev. 511, 588–89 (1994). This finding mirrors the Petitioner's analysis of the prosecutor'south jury selection techniques. Cursory for Petitioners at 39-53.

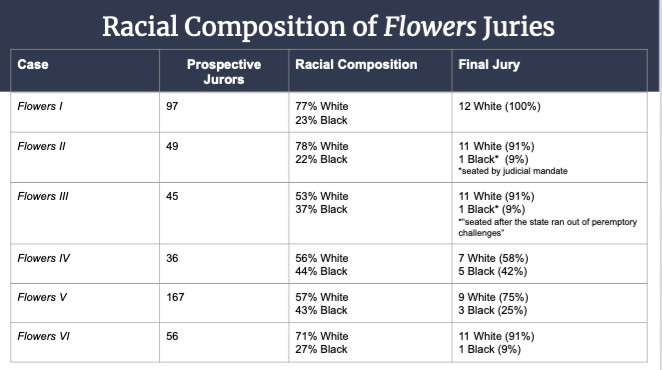

More recently, in 2018, a report in North Carolina found that "prosecutors removed nonwhite jurors at well-nigh twice the charge per unit they did white jurors." Ronald F. Wright et. al., The Jury Sunshine Project: Jury Pick Information as a Political Consequence, 2018 U. Ill. 50. Rev. 1407, 1426 (2018). This finding is consistent with Mr. Evans' behavior beyond all four of Mr. Flowers' jury trials: in Flowers I, 77% of the 97 qualified potential jurors were white and 23% were Black, and the final jury was comprised of all white jurors. Brief for the Petitioner at iv. In Flowers II, out of 49 qualified potential jurors, 78% were white and 22% were Black; after "Evans used peremptory strikes to remove each blackness panelist," the jury was comprised of "eleven white members and 1 black member seated past judicial mandate." Id. at vi-7. In Flowers Three, where "[t]hree hundred prospective jurors completed ques- tionnaires, of whom 126 (42%) self-identified equally black and 161 (54%) self-identified as white" and 54 (17 black and 28 white) were eventually tendered, Evans used all fifteen of his judicially allotted peremptory strikes to remove Blackness panelists. Id. at viii-nine. This resulted in a jury of 11 white jurors and 1 Black juror "seated after the Country ran out of peremptory challenges." Id.

For a step-past-step analysis of the jury selection procedure used in Flowers Iv, delight see this link: How did Curtis Flowers end up with a almost all-white jury?

Enquiry Findings Concerning the Effects of the Racial Limerick of Juries

Social scientific discipline indicates that diverse juries deliberate longer, consider more facts, make fewer wrong facts, correct themselves more, and have the benefit of a broader pool of life experiences and experience to draw upon and so they can meliorate sympathize the prove. White jurors are more likely to self-monitor and thus be more careful in their decision making in a diverse jury. Further, diverse juries are less likely to requite death sentences, perhaps because "minority presence on a jury allows the grouping to empathise and appreciate the different life experiences that different racial identities have with the criminal justice system. This leads the jury as a whole to perform their fact-finding tasks more effectively past helping eliminate or lessen individual biases or prejudices."See American Bar Association, Lack of Jury Diversity: A National Problem with Individual Consequences Nevertheless, the benefits of having a diverse jury are lessened when the minority juror(southward) feel like they must serve as the "token" representative for their unabridged community. Id. ("diverse juries had longer deliberations, discussed more than case facts, made fewer inaccurate statements, and were more than likely to correct inaccurate statements… People of different races—akin to people with varied economic statuses, social hierarchies, sexual orientations, or national origins—consider and evaluate the same information in different ways and often get in at different conclusions.").

More than Perfect: Object Anyway

Jeff Robinson, director for the ACLU Center for Justice, however, notes that while Batson five. KY was a "big bargain" that brought "initial elation," this excitement was apace tempered with "a strong dose of reality." A shut wait at the insights that social science theory and research may provide into this issue. More Perfect is an audio miniseries on the Supreme Court, and this episode discusses the world postal service-Batson regarding racial bias in the context of jury choice.

In a discussion on the Batson rule, Robinson specifically asserts that Batson stands to preclude "deliberate racial discrimination." Id. In recognition of this somewhat narrower interpretation, Rameswaram notes that prosecutors immediately started preparation and instruction one another on how to circumvent the Batson dominion, shortly after it came into being. Id. Specifically, Post-Batson prosecutors accept learned to cite "race neutral" reasons for excluding jurors. These race-neutral reasons seemingly accept full advantage of the inherent difficulty involved in proving racial bias. Id. For instance, in an interview with Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, Stevenson recalls being in Atlanta during 1986, where he worked at the Southern Prisoners' Defense Committee as a defense force attorney. During a trial, a prosecutor used all of his peremptory strikes to remove blacks from the jury. Afterward invoking Batson to challenge the prosecutor's decisions, the court concluded that the prosecutor's reasoning to strike i particular black juror "because she looked just similar the accused (a blackness male)" was indeed a race neutral decision. This moment pushed Stevenson to conclude that Batson only stood to make the jury-selection process "a lot more entertaining." Id.

The episode later on offers these item notable statistics:

- in the state of Washington, there have been 46-l Batson challenges mail-Batson conclusion, and among those, only i reversal. Id.

- The state of TN has non reversed a single case under Batson. Id.

- In many counties in America, the diversity of juries has non increased very much at all: (For more in-depth discussion concerning the studies referenced below, please see this NPR word);

- A 2003 report of 390 felony jury trials prosecuted in Jefferson Parish, La., constitute that black prospective jurors were struck at three times the charge per unit of whites. Nina Totenberg, Supreme Courtroom Takes On Racial Bigotry In Jury Selection, NPR (Nov. two, 2015), https://www.npr.org/2015/xi/02/452898470/supreme-court-takes-on-racial-bigotry-in-jury-selection.

- In Houston County, Ala., prosecutors between 2005 and 2009 used their peremptory strikes to eliminate eighty percent of the blacks qualified for jury service in death penalty cases. Id.

The host further considers this particularly piercing question: "the supposition...is that having black people on the jury would hurt the prosecutor. Should we just presume that?" In addressing this inquiry, the podcast brings up a study washed by The Uppercase Jury Project, that specifically looked at jury data from expiry penalty cases. Later on looing at information from 353 cases in xiv states, they establish that white men are vii (7) times more probable to want the capital punishment as blacks are. (Capital Jury Project Study)

In some respects, statistics regarding the inefficacy of the Batson dominion at preventing race-based jury selection is huge: these are hard, undeniable numbers, asserting that race-based jury pick happens frequently and is detrimental on a vast scale. On the other hand, those attentive to this detail issue probable already know about America's race-based jury selection trouble, and perhaps Batson'south lacking role. In looking to Stevenson'due south anecdote, it seems the platonic trial practices in a mail-Batson earth are those which recognize that parties in a particular litigation can non only exist overtly bias, but too implicitly-biased. If a prosecutor is deliberately aiming to create an homogenous jury, a gauge should recognize that their own willingness to condone that prosecutor's reasoning as "race-neutral" may exist subject to unconscious viewpoints that they themselves may go along and carry into their roles as judges.

Racially Diverse Juries Promote Self-monitoring Efforts During Jury Deliberation

Stevenson found that "interracial interactions produce anxiety among dominant group members, due to a fear of behaving prejudicially. In plow, feet promotes self-monitoring strategies during interracial interactions, reflecting attempts to avoid expressions prejudice. In the present inquiry, nosotros investigated the effects of jury racial composition (all White vs. racially mixed) on mock jury deliberations, expecting that interracial juries will trigger social anxiety, self-monitoring, and in plough, macerated communication with fellow jurors (i.due east., discussion count). Testing these hypotheses, mock jurors' online text responses ostensibly explaining their verdict preference to either a racially diverse or all-White jury were subjected to text analysis via Linguistic Enquiry Discussion Count (LIWC) software. Supporting hypotheses, mock jurors spoke significantly less (used fewer words), still simultaneously spent more than time developing their response in racially mixed juries than all-White juries.The upshot of jury racial limerick on discussion count was serially mediated by fewer social words, and in turn, greater use of first-person atypical pronouns in racially various juries, probable reflecting increased social anxiety and cocky-monitoring efforts in interracial contexts.

At that place are several potential weaknesses of this study: commencement of all, a mock jury does non always generate a result accurate in existent life. In addition, the mock jury deliberation occurred online, leaving open the question of whether the results of this experiment are applicative in face up-to-face deliberations. Furthermore, it's unclear how the researchers could brand the participants enlightened of the race of the other simulated jurors without letting them know the research is about race.

In this study, participants were presented with a murder and robbery case; farther enquiry is required to determine if the dynamic Stevenson found carries into other types of cases. Boosted research could too clarify the other the other implications of various juries, and the effects of "watchdog syndrome" and tokenization.

Diversity's Impact on the Quality of Jury Deliberations

The goal of this study to determine whether diverse juries engage college quality deliberations than non-diverse juries. Researchers conducted mock trials to determine with varying the strength the bear witness with various and non-diverse juries. They plant that "participant race did not affect the quality of deliberation contributions, suggesting that diversity similarly affected participants of both races." This finding is somewhat different than that of Sommers (2006) and also suggests that diversity'due south impact goes beyond the watchdog effect (Fleming et al., 2005). Minorities benefiting from variety does not rule out the possibility of the watchdog event, only it does propose that diversity might operate through other mechanisms as well. The results from the current study advise that variety might improve deliberations because of the heterogeneity of experiences and perspectives (Nemeth, 1986), rather than from a reduction of prejudice. Information technology is also possible that diversity's benefits operate differently for minority and majority group members."

This is some other mock jury study, thus may not exist like the existent thing. Withal, the jurors were presented with a video case (factually based on a real case) and actually deliberated in person, which creates a more than realistic experience. In addition, the distinction between weak and strong evidence may non be clear. The question remains: can the participants distinguish between good evidence and bad evidence? Importantly, the study simply used blackness and white participants. To make a jury diverse, researchers included a minimum of 2 non-whites. This might non be true multifariousness, even if there is a strong white majority. Also, sizes of jury not consequent. No less than four, no greater than seven, with the size varying each fourth dimension. Finally, the jury was only given 45 minutes to deliberate before declaring information technology hung. This is unrealistic as real juries has much more than time than this. Cutting deliberations short might've non shown the true results. The responses were coded for quality by inquiry assistants, some of whom had knowledge of the hypotheses and theme of the study. This coding method could influence the results.

In dissimilarity, Sommers found that "the quality of deliberations measures did provide some support for diversity'southward benefit, with jurors in diverse juries providing more than units with instance facts and more sufficient arguments than jurors in not-diverse juries. Additionally, jurors in diverse juries were more likely to deliver counterarguments and discount show lacking in reliability than jurors in non-diverse juries. The finding of higher quality contributions from jurors deliberating in diverse juries is consistent with previous enquiry examining jury deliberation content." (Sommers, 2006).

Consequences of Jury Racial Diverseness: Empirical Findings, Implications, and Directions for Hereafter Research

Multiple studies propose that Justice Marshall was right in Batson to assume that a jury's limerick has the potential to affect trial outcomes. The investigation of Baldus et al. (2001) into capital juries in Philadelphia indicated that—consistent with the assumptions of the attorneys in the trials analyzed—racial composition was a reliable predictor of jury verdicts. The Bowers et al. (2001) analyses described higher up led to a similar conclusion, namely that the greater the proportion of Whites to Blacks on a capital jury, the more likely a Black accused was to be sentenced to death, especially when the victim was White. Such patterns are not bars to the White/Black dichotomy: Daudistel, Hosch, Holmes, and Graves (1999) examined 317 nonfelony juries in Texas comprised of Whites and Latinos, and determined that bulk‐White juries were harsher in their judgments of Latino defendants than were majority‐Latino juries.

Mock jury experiments have produced like conclusions to these archival analyses. In 1 such study using college students, Bernard (1979) manipulated the race of the defendant in a trial video presented to 12‐person mock juries of differing racial compositions. Across conditions, White jurors were more likely to vote guilty than were Blackness jurors, particularly when the accused was Black. Indeed, out of ten mock juries examined, the only one to attain a unanimous guilty verdict in the written report was also the only all‐White jury to view the trial of a Black defendant. Of course, one practical challenge faced by mock jury experiments is that the n for statistical analysis equals the number of groups in the written report, non the number of individual participants, and the pocket-sized sample size of the Bernard (1979) experiment prevented statistically reliable group‐level findings. See as well Variety and Citizen Participation: The Effect of Race on Juror Determination Making ("we detect that Black defendants are less probable to be convicted by juries composed of a college percentage of Blackness jurors and are more likely to be convicted by juries composed of a higher percentage of White and Hispanic jurors.")

The notion that white jurors are more than likely to convict Black defendants was certainly the instance in Flowers: in his beginning three trials, where the jury was comprised of 12 white jurors or 11 white jurors and 1 Blackness juror, the jury returned a verdict of guilty with a sentence of decease. Withal, in one case more Black jurors were included (v in Flowers IV and 3 in Flowers V), the jury could not achieve a consensus, resulting in a mistrial. Simply put, "[t]he racial census of the first five Flowers juries correlates with the results of their deliberations." Brief of Amici Curiae of the Magnolia Bar Association, et. al. at 22; this decision is consistent with the results of the Bradbury & Williams study.

On Racial Diverseness and Grouping Conclusion Making: Identifying Multiple Furnishings of Racial Composition on Jury Deliberations

The abstruse explains that "this inquiry examines the multiple effects of racial diversity on grouping decision making. Participants deliberated on the trial of a Black defendant equally members of racially homogeneous or heterogeneous mock juries. One-half of the groups were exposed to pretrial jury selection questions about racism and one-half were not. Deliberation analyses supported the prediction that diverse groups would exchange a wider range of information than all-White groups. This finding was not wholly attributable to the performance of Black participants, equally Whites cited more case facts, made fewer errors, and were more amenable to discussion of racism when in diverse versus all-White groups. Even before discussion, Whites in various groups were more lenient toward the Black defendant, demonstrating that the effects of diversity do non occur solely through information exchange. The influence of jury selection questions extended previous findings that blatant racial issues at trial increase leniency toward a Black defendant."

Once again, this was simply a mock jury and may not produce results accurate and/or applicative to real juries. However, participants were pulled from an active jury puddle and placed into a realistic courtroom simulation. Withal, a majority of participants were female. Besides participants know they are in a study about jury determination making, which ways they may not honestly reply the racial voir dire in order to remain in written report and get paid.

Race, Diversity, and Jury Composition: Battering and Bolstering Legitimacy

In cases similar Flowers, perception matters. Based on the historical assay offered past the EJI, all-white juries passing judgment on cases involving Black lives leads to a decrease in community support for the criminal justice system. Equal Justice Initiative, Illegal Racial Bigotry in Jury Choice: A Standing Legacy (2010) at 40-41. Conversely, people trust institutions they perceive to be fair, with racial balance equally a factor in determining fairness. Id. The ABA explained, "a heterogeneous jury not just confirms that the organization is fair and impartial for the defendant… but besides assures the public at large… Conversely, a racially homogenous jury puddle can have a harmful touch on the public's perception of the justice arrangement."

While deliberations of racially or ethnically diverse juries can be enhanced past the wealth of diverse experience the jurors bring to them, they tin endure serious losses if jurors feel they are charged with representing a particular constituency in the jury room. In past high-profile cases involving racially charged crimes, the perception of an unjust system has driven people to violence. Equal Justice Initiative, Illegal Racial Discrimination in Jury Selection: A Continuing Legacy (2010). For instance, people took to the streets in protestation and, later, to riot later four white police officers were acquitted after beating Arthur McDuffie, a Black human from Dade Canton, Florida, the Governor'southward commission convened to look into the thing constitute that the riots were a result of both "racism and the blacks' perception of racism." Id. at 38, accent added. The famous Los Angeles riots after the trial of the police officers who shell Rodney King in 1992 were fueled by both police violence against Blackness community members and by the makeup of the jury who acquitted the alleged perpetrators: ten jurors were white, one was Asian American, and ane was Latino. Id. at 39. Since then, "[i]north Long Island, New York; Jena, Louisiana; Powhatan, Virginia; Panama Metropolis, Florida; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, recent verdicts past all-white juries or by juries perceived as unrepresentative have triggered widespread unrest and outrage in poor and minority communities where serious concerns almost the fairness and reliability of the justice system have emerged." Id., internal citations omitted.

Mr. Flowers' case hasn't attracted much in the mode of public demonstrations, simply his case has caught the attention of a wide diversity of media outlets, from the New York Times to the International Socialist Review. It was even featured on an episode of the popular podcast "In the Night." People who larn about Mr. Flowers from the news coverage that comes from a SCOTUS example and who see racially exclusive juries every bit problematic will probable see the justice system overall as less fair and legitimate; they may manifest this view through riots, protests, or silent erosion of their trust in the justice organization.

Mapping the Racial Bias of the White Male Capital Juror

In Mapping the Racial Bias of the White Male Capital Juror, researchers found that "[westward]hen they judged a blackness defendant—and essentially merely then—they diverged significantly from their peers, both in terms of how they constructed the defendant's answerability and motivation, and on whether they believed he deserved to be allowed to continue to alive… the kinds of crimes that give ascension to capital letter prosecutions non only provoke heightened levels of anger and fear among jurors but besides are more likely to activate cultural stereotypes well-nigh minority ethnic and racial groups" and the more "stereotypically black" the crime or the defendant was perceived, the more likely D got a death penalty. These stereotypes even affect criminal justice professionals' perception of the sentence defendants should get." It cites a report showing that "decease‐qualified jury pools are disproportionately white, male, older, and more religiously and politically conservative," and citesstudies showing that "support for the death penalty among whites is highly correlated with measures of anti‐black racial prejudice and stereotyping." This finding tracks onto the juries that Mr. Flowers faced in his showtime iii trials that were all-white or almost all-white, all of whom sentenced him to expiry.

Jury instructions in uppercase cases are also typically difficult to understand, which too activates utilise of racial bias in decision making. In addition, empathy is of import to mitigation, and jurors feel less compassionate to people they perceive every bit unlike. The white male jurors in this study judged a black defendant whom they tended to view every bit driven by the defendant's own depraved predispositions, and as someone whose criminal behavior they were reluctant to translate as the production of the defendant'due south dysfunctional and psychologically damaging background. As a outcome, these jurors gave significantly less weight to the mitigation that had been offered in club to place the defendant's behavior in a broader and more than sympathetic context. White male person jurors too saw the black defendant as less redeemable, in that he was viewed as more than cold‐hearted and remorseless, and as someone who would exist more than probable to re‐offend if given the gamble. Furthermore, these furnishings were axiomatic despite the fact that White male participants had significantly higher comprehension of the capital jury sentencing instructions, something our prior inquiry indicated should have, if anything, moderated racially disparate outcomes and suppressed the between group differences."

The written report went on to explain "a concentration of white male jurors sitting in a black accused's penalty trial appears to undermine the jury'southward willingness to consider the instance for mitigation. Consequently, ensuring some representation for nonwhite capital jurors may not be sufficient to deliver a truly fair, various, and impartial jury. Because the procedure of minority exclusion is a cumulative one—resulting from the fashion in which venire pools are constructed, jury eligibility is determined, and decease qualification and jury selection are conducted—there is still a high probability that the juries that are finally impaneled to hear and make up one's mind a capital case will be susceptible to the kind of white male juror bias that we have uncovered in this study." The fact that racially inclusive juries produced mistrials, not acquittals, suggests that Lynch & Henay are right that white male juror bias can notwithstanding impact diversified death-penalty juries, like those in Flowers Iv and Five.

Conclusion

Social science supports the underlying assumption in Batson and its progeny that lack of jury diversity disadvantages defendants of color. The all-white and bulk-white juries in Flowers had an effect on the effect. This event was to Mr. Flower's detriment, and may have contributed to his capital sentencing. The Supreme Court should rule with the understanding that any Batson violation aversely impacted the Petitioner in Flowers five. MI.

What Was The Racial Makeup Of Most Of The Free People Of Color?,

Source: https://courses2.cit.cornell.edu/sociallaw/FlowersCase/racialmakeupjuries.html

Posted by: falktrocce.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Was The Racial Makeup Of Most Of The Free People Of Color?"

Post a Comment